Trout Identification / Salmonidae

Rainbow Trout / Oncorhynchus mykiss

Associated with the West Coast drainages, the Rainbow trout inspires reverence world wide since its stocked introduction to Japan, South America, the East Coast, Europe and New Zealand. Known for its fighting spirit and aerial acrobatics, the Rainbow trout is distinguished by its pinkish broad band along its lateral line and sometimes as far as its gills and cheeks. It is not uncommon for Rainbows living in deeper water to display orange and lavender hues at maturity. The other striking characteristic of this trout is the greenish bronze back and sides which are dotted with small black spots. The Rainbows underbelly is whitish or silvery. During the spawning period the males develop a hooked jaw, (oncorhynchus) and the rainbow pink darkens into a defining red. Also known by sportsman for its propensity for growth, especially in larger waters, the Rainbow has a sea-run member of its family in the steelhead of the West Coast. A variety of regional Rainbows are identified such as British Columbia's Kamloop rainbow and specific drainage strains such as the McCloud River strain or the Kern River strain.

Habitat: Although the Rainbow trout has been cultured in breeding programs for a variety of water conditions, its preferred water is cold, clear oxygenated waters, particularly fast riffles and good flowing runs. It prefers water temperatures from 55 to high 60's.

Food sources: Ranging from zooplankton to forage fish, Rainbows feed most heavily on insect life in streams and rivers.

Spawning: Depending on the geographical zone and water conditions, Rainbows begin spawning as early as March, but more typical are the months of April through June. Rainbows are extensively stocked in the Eastern Sierra Mountains.

Cutthroat Trout / Salmo clarki

Covering a huge expanse of territory in the West, the Cutthroat is native to the southwest in the high plains and deserts of Colorado, Utah, Nevada and New Mexico to the over thrust of the Rockies in Montana to the Pacific estuaries and as far north as British Colombia. Although not noted for the fighting qualities of its close cousin the Rainbow, the Cutthroat is a revered trout in these regions so much so that in some parts of its range it is simply referred to as the native trout. The Cutthroat trout has many variants and sub-species, and it is known to cross-hybridize with the Rainbow trout. As its name implies, the Cutthroat has a bold, orange slash across the lower jaw which most easily identifies this as a singular trait of recognition. Marked with small black spots on its back and extending to the tail, the Cutthroat often displays a soft, golden or orange hue across its sides blending into a greenish, gray back. It too has a sea-going member in its family along the costal waters of British Columbia down to the Oregon shores. Unlike the steelhead, sea run Cutthroat tend to stay close to their home waters preferring the sanctuary of coastal estuaries.

Habitat: Cutthroats prefer colder water and do not adapt well to habitat degradation or competition from non-native species. Unlike Rainbows, Cutthroats tend not to grow as large as Rainbows in rivers or lakes. Although they can survive up to eight years, they rarely exceed eighteen inches in streams and rivers. They prefer deeper pools and good bank cover. One of the last strongholds for westslope cutthroat can be found on Montana's South Fork Flathead River.

Food sources: Insect life

Spawning: Similar to the Rainbow, the great majority of Cutthroats spawn once in their lives. They spawn from March through as late as August. Like Rainbows they prefer shallow, fast water for their spawning beds in small stream tributaries. They do not reach sexual maturity for two to four years.

Brown Trout / Salmo Trutta (salmon trout)

Closely identified with the Atlantic salmon and a native to Europe, the Brown trout is often associated with Germany and previously referred to as the German Brown, no doubt due to its importation by a New Yorker and a German immigrant in 1883. By 1889 the Brown Trout was being reared and stocked as far away as Montana. Initially the cries of protest were muted when opponents realized that the industrialized East had destroyed habitat for the sensitive Brook Trout. In its place the German Brown survived in warmer waters with some degree of pollution present. Pioneers in the art of fly fishing in Pennsylvania and New York discovered that the Brown trout rose readily to a dry fly, although it was more challenging to catch than a Brook trout, not doubt aided by the fact that larger Brown trout feed at night. Brownish overall, the sides are yellow-brown and are dotted with large dark spots towards the back, which in turn are ringed by a lighter hue. Along the lateral line are reddish-orange spots. The fins are clear.

Habitat: Brown trout prefer slower water, although they do survive and prosper in freestone rivers. They tolerate warmer water with greater silt concentrations than any other trout, but they too become stressed as water temperatures reach 70. They can live ten to twelve years in the wild and compete with the Rainbow trout for trophy status, especially in lakes and reservoirs. With the advent of whirling disease, the brown trout has resisted the disease and done very well in Montana's Madison River and Rock Creek.

Food sources: Aquatic and terrestrial insects, crustaceans and other fish.

Spawning: In drought sensitive Western states, Brown trout have a distinct advantage in that they spawn in the fall from October to February. Reservoirs are dewatered for irrigation and drawn down. By fall the irrigators have shut the gates. When the Brown trout move up the tributaries, they are spawning in running water that will soon be replenished. Instead of having their redds dry up during the late spring and summer, Brown fry have already emerged and begin moving to deeper water. Brown trout also have sea-run relatives both in Europe and the North Atlantic coast. The Brown trout is also stocked throughout the Eastern Sierra Mountains from Lone Pine to Bridgeport.

Brook Trout / Salvelinus fontinalis

Called the Square Tail and the Speckled Trout, the Brook Trout is no trout at all. Rather it is a member of the char family, but science will not dissuade generations of anglers from early colonists on who call this favorite trout, just that, a trout. Much like the canary in the mine, the brookie, just like the Bull trout, is a bell weather warning against pollution and high levels of suspended sediment. Tending to be small in length, with the exception of Brookies found in Canadian lakes, the Brook trout, nonetheless, is admired for its beauty from Maine to California in the few remaining, unspoiled wilderness streams and creeks. The back tends to be a dark melding of brown and green with dark vermiculations from head to tail. Worm-like in appearance, the vermiculations resemble a maze all the way across the back. The sides are variations of green with some gray, along with distinct red dots surrounded by blue halos. The belly of the Brook trout ranges from pale yellow to pinkish orange and is muted with streaks of lead pencil shadings. The fins are lightly shaded hues of orange accented with white tips. The anal fin and the caudal fin display dark blotches.

Habitat: Found in cold, clear mountain creeks and spring-fed streams, Brook trout favor shore cover, especially where spring water filters in to the stream. Brook trout do not survive very well in water temperatures above 65. Many small creeks and high elevation lakes in the Sierras and Cascades are home to the Brook trout.

Food sources: Aquatic and terrestrial insects, crustaceans and other fish. Preying on caddis worms and crustaceans, the Brook trout's efficient digestive tract empties in less than a half hour. A pan size brookie won't hesitate pouncing on small minnow.

Spawning: The Brook Trout spawn in the fall. Usually they spawn in their second season. In high elevation lakes and streams with very cold water, Brook trout tend to become stunted and may reach sexual maturity at five or six inches! They may also cross with a Brown trout creating sterile Tiger Trout.

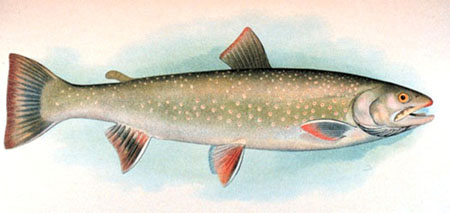

Dolly Varden / Bull Trout

Salvelinus malma / Salvelinus confluentus

Although the Bull Trout in Montana has recently been classified as somewhat distinct from its coastal cousin the Dolly Warden, both fish are similar in appearance, and both are char rather than trout. They are closely related to the Arctic char. Today the range of both fish is shrinking. Typically found along coastal streams of Oregon and Washington, the Dolly Varden is an important game fish in Alaska as well as Kamchatka, Russia. The origin of its colorful name may be disputed, but during the 1870's a Dolly Varden was a fanciful dress in the fashion world, and later a large, flowery hat earned the praise of the fashion world with the same name. Charles Dickens used Dolly Varden for one of his characters.

The Dolly Varden coloration varies a great deal, buy typically they have dark green backs or a bronze coloration which pales as it merges with the lateral line. From the lateral line to the belly the Dolly is often a light green or a pencil lead gray. The belly is whitish. Scattered across its sides, but not on the head or tail, are pale yellow or pinkish-yellow spots. Scattered within these dots are some small red dots on the lower sides.

Habitat: Bull Trout seek out cold, clear water, and they can not tolerate high sediment levels. They may inter-breed with Brook trout, but their off-spring are sterile. Dolly Vardens are anadromous and prefer the lower reaches of tidal rivers and estuaries. Resident and land-locked Dolly Varden and Bull Trout can weight up to twenty pounds and exceed thirty inches in length. Sea-going Dolly Vardens in Alaska typically reach ten pounds and devour spawned salmon eggs and salmon fry.

Food sources: Dollies and Bull trout are slow growing during the first few years when they feast on insects, aquatic invertebrates and crustaceans. As adults they become voracious piscivores.

Spawning: They spawn in the fall, but they do not reach sexual maturity for four to five years. Even resident Dolly Vardens and Bull trout are migratory by nature traveling long distances to spawn as well as moving for seasonal water adjustments.

Lake Trout / hungri-devili (a joke!)

Salvelinus (char) namaycush (American Indian name for Lake trout)

This Big Mac, often called Mackinaw trout in the Rockies, has only one relative in the salmon family who gets bigger, and that is the King Salmon. In actuality they are a char. Prior to the devastation of the Lake trout populations in the Great Lakes due to the Lamprey eel, commercial fisherman caught some of these big devils upwards to eighty pounds. Slow in growth with a life span of twenty years, these monsters of the deep eat a lot of trout in a given year. Yellowstone Park biologists estimate that each rogue Lake trout eats over 50 Cutthroat trout a year. Multiply that by many thousands of Lake trout and it is no wonder the Cutthroat population in Yellowstone Lake has plummeted 70% since some bucket biologist, in the words of the former superintendent, perpetrated "an appalling act of environmental terrorism."

The Lake trout is a native of North America inhabiting deep, cold lakes. They thrive in lakes that reach depths of two hundred feet. It has the most forked tail of all its cousins in the trout family. Its back ranges in the gray-green tones to soft bronze, and its belly, depending on the water, can be silverish-white to lead-pencil gray. Large irregular, light-colored markings stretch across the sides, while its back has feint vermiculations similar to the Brook trout. Light speckling may be observed on the dorsal, adipose and caudal fin. Similar to the Brook trout, it has a white edge on the pectoral, pelvic and anal fins.

Food sources: Lake trout are slow growing during the first few years when they feast on zooplankton, insects, aquatic invertebrates and crustaceans. As adults they become voracious piscivores as biologists from Montana will attest.

Spawning: They do not reach sexual maturity for six to seven years. They return to the same spawning area of the lake in which they were spawned. They do not build nests and let their eggs free-fall to boulder or rock strewn bottoms in water depths of from ten feet to a hundred feet. Throughout the year they prefer cruising in the deep, but in the spring time they move to the shoreline and devour other fish.

Sources

Familiar Freshwater Fishes of America by Howard T. Walden, published by Harper and Row, 1964.

http://www.fish.state.pa.us/pafish/fishhtms/chap16.htm

http://fwp.mt.gov/fieldguide/detail_AFCHA02090.aspx